Many of us might consider ourselves global citizens; it’s an attractive idea, the sense of feeling connected to, and responsible to, something larger than ourselves. But what does that look like on a local level? How do ambitious dreams translate into the intentional actions that will get us there?

For our inaugural big interview, we sat with Prophet Walker, Co-Founder of Treehouse Co-Living, to talk through global minded contexts, neighborhood, impact, why the houseless crisis is an acute philosophical crisis, and the virtue of community as a verb, not a noun.

ASSEMBLAGE defines being a global citizen as somebody that’s globally minded that’s making courageous decisions about things that benefit oneself, one’s neighbor, and one’s planet. So with that, talking to you about your background, how you arrived at this particular moment in your life and how you arrived at the concept for Treehouse.

So I’ll start by saying that I grew up in a multitude of different worlds. I’m half white, half black. On the white side of the family I had the experience of looking at extreme levels of racism, serious levels of wealth, and drug addiction. And on the black side, I had the experience of owning, for instance, my great grandfather’s ‘freed’ papers, watching black entrepreneurship in Los Angeles, the drug trade up close and personal. It’s sort of a story of redemptive healing in a hood that’s marred with gang violence and poverty.

And which area of Los Angeles was this?

So I grew up in Watts, South Central area, but I was born in Beverly Hills. My mother unfortunately became deeply addicted to heroin. Everything just sort of unraveled for her, about the time I was, I’d say five or six.

What was simultaneously happening is that we were in the throes of early 90s Los Angeles. This is the point at which the crack cocaine epidemic started to unravel at the seams, and it went from a purely sort of entrepreneurial, very controlled economic venture, to one of territory, war, the development of gangs. A wild amount of guns flooded into our communities. My family was close enough that I experienced the ride of what that meant.

There was this sort of cultural zeitgeist thing that was happening in the hood, that was telling me and my friends to get up and get out. That was our goal: to leave the hood. And while in South LA and Watts I couldn’t leave, so I had to lean into my environment. And in that environment my friends and I would build club houses and tree houses; we needed an escape. So this is sort of the evolution of the name Treehouse.

My dad was very crude, sometimes, in his lesson choices. I remember we were driving, I was 10 years old, through South LA and people are fighting in the streets. And we’re what he calls ‘rubbernecking’ and he’s saying “Stop Rubbernecking. Listen. The lesson I want for you is ‘You’d rather hear about it, than be about it’. But we kept looking – my cousin and I we kept looking – we got to the gas stations and he’s like, “ We’re going to go back and I’m gonna show you that you’d rather hear about it than be about it. Keep your eyes straight. Stay focused. Protect your community, don’t worry about tangential stuff.”

So we went back and one of the gentlemen who was fighting had been murdered. Right in the middle of the street. And my dad’s like, “This is life or death, where you’re at. Your goal is to build your community out of it. Not add to the gossip. Not add to the chaos. Stay focused.”

To escape those realities we legitimately built clubhouses. We would go find scrap, from the alleyways, to build our club houses. And then we started getting a little more sophisticated and started finding wood to then start building just platforms in the city streets. But every single time, whether it was the city, or whether it was the parents, somebody would tear our shit down. They would be like, ‘this is a hazard’. And they were right, it was a hazard. You would see us pulling mattresses down the streets, like dirty mattresses.

Rudimentary architecture. [both laugh]

I remember we had gotten it torn down completely and my grandfather said “Just build it on wheels. And then when they say that you’ve got a day to tear it down, just roll it out of here.” I was like, ‘BRILLIANT’. So we went and we robbed grocery carts and created a movable clubhouse. We literally would pull this thing from parents house to parents house to parents house. And what I learned from that then was like, in this sort of “clubhouse”, if you will, it wasn’t about exclusivity for exclusivity sake. We had an idea of what peace looked like, and we wanted to maintain that. And anybody on our street, or other streets, was welcomed, in so far as you didn’t disrupt that.

Right; the entire point of this was to build this sanctuary, this peace, to contribute to the community as a respite, as an escape, without having to leave.

Without having to leave. And it was as simple as, like, “Are you a nice person?” Just that simple. Kids aren’t dealing with the dogma of ‘what’s their political beliefs?’. That’s not their view. They’re just like, “Are you a nice person?”

There was still gun violence, shootings. All of this is happening. I’m 12 years old when one of my closest friends, David, is gunned down. We’re a few feet from one another. From shock I end up chasing the gunman (without a gun, which shows I was in serious shock). The gunman got away.

We were there left with what to do.

I remember the most powerful thing that happened in that moment. Every single person on our block, every household, came up. Every single mother, every single father, every single kid, grandmother took turns holding me and my friends. Were out there for hours. And not one person in the community would let us not get a hug, would not remind us that it would be okay. And every single day after that for the next year or two someone would make sure. I could not walk down my street, without “Baby, are you okay?” “Baby where’s your head at today?” “Come here, let’s eat.” “Let’s sit and talk.” “You’re going to be alright.” “Are you afraid?” The men who didn’t know how to fully express love would ask “Are you solid, my G?” “Where’s your head at?” “Are you afraid?” “Do you want to learn how to fight?” It was their way of saying, “You’re going to be okay.” And this community, no matter how f*cked up the world perceives it, this community has you. It has love for you.

Community isn't always sexy. It isn't always the next fireside chat. It isn't always how we're going to see the next marketing experience at Soho House. It's just not. It's much, much deeper than that.

Which is a really powerful thing to see, like in your formative years of life: community, as a noun, but also community, as a verb. And, you’re one of the few people that knows the embodiment of community as a verb, internally. And that’s not a common experience, for everyone.

That’s what I think ultimately gets me to Treehouse, right? It’s these key moments of looking at community as (to your point) a contact sport. Community isn’t always sexy. It isn’t always the next fireside chat. It isn’t always how we’re going to see the next marketing experience at Soho House. It’s just not. It’s much, much deeper than that.

Then at 16 I get incarcerated. What I thought would be fully a normal day in South LA. You heard what I’m dealing with at 13. Getting in a fight, breaking someone’s CD player? This is par for the course! But today wasn’t that day. I was incarcerated and I learned a lot about our justice system.

After the fact, I remember writing that during my sentencing in the courtroom felt like my mortuary and the jumpsuit like my casket.

I would learn more in depth about the ridiculousness of our justice system. And the biggest thing that I learned was how effectively creating ‘others’ out of human beings could drive fear. And fear would result in wild, terrible consequences.

The othering of people like “Oh, you’re not part of this particular thing” or “You can’t be in this community” or whatever…

In the words are the millennial: ‘like mindedness’. It seems innocuous until you start having extreme woke politics and extreme conservative politics, and we don’t see, actually, day to day how that impacts our biases.

Put a pin in that, because it was actually something further down I want to talk to you about that part. But when you talk about coming through that experience and then the campaign that you did. All of these are parts that got you here.

Going through the prison experience, I started one of the largest college programs in America. I wrote Governor Schwarzenegger a letter of how we could restructure prison and suggested that there should be a college dorm inside prison. My first foray in ‘built community’.

There’s a Nipsey Hussle line that I love, which is, “He grew up knowing that he was a genius / but he’s left with no platforms to explore.” I felt the same way about people there, because they were the ones teaching me. My cellmate taught me English. My next door neighbor was a MIT professor that got in a bar fight. He taught me math. I saw genius in there, but they’re not given the options.

Prison was exiling people from their communities. Luckily, inside a whole different community, a microcosm, was happening.

And that’s what I wrote to the governor: that there’s a tremendous amount of energy here, that if harnessed differently, could produce a tremendous amount of success. That program started with 30 people in the dorm. We would debate philosophy. We would talk about going to Mars, teach each other chess. We taught each other how to play instruments. So many beautiful conversations. We were breaking down racial barriers which in prison is Jim Crow South. There are literally water fountains, benches for race, but we’re breaking that down in the dorm. I think there are now 30,000 plus people in that program. You’re able to get a two-year or four-year degree prior to coming home and be a contributing member to society.

California’s recidivism rate is about 75-80% on its own. If I, anybody, ran a company like that, should close tomorrow. That level of failure. With the college program we started there’s less than half a percent of people that recidivate and go back to prison.

I came home and went to Loyola Marymount to study engineering, and was wrapped in community there too. I was realizing that we needed community on the outside as well. So we created a nonprofit ARC, which is, I think, the largest one certainly in Los Angeles but –

And ARC stands for

The Anti-Recidivism Coalition. All of your recent laws that you’ve probably seen passed in justice reform, whether it’s prop 57, prop 47 or getting [LA county District Attorney] George Gascon elected, much of what Kim Kardashian is pushing, all of that is ARC.

When it was envisioned ARC was to be wholly run by formerly incarcerated people, making sure that there was a nonprofit that provided people – or an entity that provided people community first; and actual tangible resources to do great.

So had just had this very successful physical community in prison, the worst of circumstances. Then I came home, and within a month and a half I walked onto Loyola’s campus. And I’m thinking, “Where on earth did they make all these beautiful people? All these beautiful trees? There’s grass!” “What is happening here?” And my desire for design and aesthetic and how that changes your spirit became so palpable.

And then I stepped into my professional life which was just building construction and utilizing my engineering degree.

California's recidivism rate is about 75-80% on its own. If I, anybody, ran a company like that, should close tomorrow. That level of failure. With the college program we started there's less than half a percent of people that recidivate and go back to prison.

So. Ace Hotel.

So. Ace Hotel is a moment where we’re on a 300-person project that I’m managing on any given day. The mental gymnastics of that is, first of all, one of the greatest addictions I’ve ever had. I could walk on a floor in the morning and there were just studs, and by two o’clock the whole thing is drywalled. Just transforming.

Ace Hotel was different. In that it was… it was new. It was hip. It was decadent. It was sort of at the cutting edge of culture in downtown LA. The entire street was desolate while we were doing construction and it began to change little by little as we got closer to ending construction. They were having a lot of fun and they were doing so in beautiful design, with nature and trees around in an otherwise barren space.

That was the beginning of me thinking “I want to build one of these one day”.

Meanwhile the local Assemblyman is termed out; all these whoo-ha’s start jumping into the race to represent Watts and Compton and Carson and South LA and Playa Vista. I think, “the interest of Playa Vista is going to be the interest of this politician” and everyone that jumped in didn’t have the backbone for what’s needed for this community. Their hands were tied by whatever resources being given to them because there’s a lack of resources.

Beverly Hills is going to elect what’s in the best interest for them and for the politician in Watts. The people in Watts cannot fund the campaign. Period. That’s to me the dirty money of politics. It’s not that money is in politics, it’s that money is unequally distributed in politics. Those who cannot raise money, those who do not have support will not be beholden to their community.

And so I looked at that and I was like, “Nah, I want to rock for my community.” And if I have the audacity to run, being formerly incarcerated, I’m already signaling ‘fuck the establishment, I’m going to do this my way’.

So what year was this again?

This was 2013. I set up this grassroots community campaign, naive as it gets at 25, thinking we’re gonna run the state. [laughs]

But also, that was your training, your community service. What the result was; did you…?

So I won the primary, lost the general, and it was a big thing. It was fascinating actually what happened. Initially I couldn’t raise money for the life of me.

Then something switched. I started leaning in, more and more of like, “This is who I am, this is what I believe.” I realized that the power of being elected wasn’t just the ability to sign a law but it’s also the power of influence.

Which is pretty much the linchpin of any community, which is: how do you mediate across biases? How do you create a space that fosters that kind of thinking, and encourages space for that to grow? But it also goes back to what you’re talking about with design, and leading with that part of it. If you could do this with a school, after doing it with Ace, and having the audacity to run for office because you just thought it was a good idea to show what that looks like? Well then it makes sense how you end up with a place like this.

Yeah, I got sick from running for office. There’s many issues in the world, many of which I think about that I care about, but I don’t waste a second of my time talking about them unless I want to do something about it. Period.

Otherwise, what’s the direct impact that I’m willing to commit.

Correct. If I’m not [willing to commit] shut up, it’s not my business. I’m rooting for those who are in it. Otherwise it’s not my business.

And that was my thinking with running for office and then bringing people together for the summer camp. I thought “I want a summer camp for kids in South LA.” I remember negotiating with law enforcement, and the OG’s from the hood. Law enforcement was like, “P; we have to be the camp counselors.” And the homies from the hood are like, “P, we have to be the camp counselors. We know these kids.” And I’m like, “…All of you. I would never send my daughter to a camp with the homies from the hood, and the police, period. [laughs] I would send my daughter to a summer camp with some 18 year old college kid who’s obnoxiously happy about butterflies.” I want that level of happiness to be exuded, and their light and their belief in dreams to flow through. And I thought “if you guys want to rock with me, we can all do that together, and we can wrap our arms around these children feeling love.” That’s community.

We have four housing projects in Watts. All of these housing projects are rivals. The children go to elementary schools that are very specific to the housing projects so they never interact with one another. And then middle school happens and there’s only one middle school…

…and they’re all thrown into it…

…and they’re all thrown into that one middle school. There’s the history of gangs in each that these kids are learning and it’s a powder keg. That kid no longer gets to dream. They’re dealing with the reality of cousin or uncle who got murdered 10 years ago so therefore, I’m mad at your hood. That’s what we’re dealing with – mad at tribes now.

I call my boys at the Harold Robinson Foundation summer camp and I say let’s do a Watts United Weekend. Let’s bring kids from those housing projects, let’s bring their parents. Let’s bring law enforcement, let’s bring the community OG’s, let’s bring the happy funny camp counselor, I want the Governor here if I can, I want anyone who claims that they have interest and alignment with this community at this camp. We’re going to do breakouts about what we’re going to do to sustain our community, not what other people are going to tell us.

It ended up being one of the most powerful times of my life. When all of the community came together, all of these otherwise warring factions. Law enforcement wasn’t allowed to wear their law enforcement gear. Homie from the hood weren’t allowed to wear their Dickies. Anything that was your uniform indicative of who you thought you were? No. Put on some shoes and some shorts and we’re about to do mud fights, we’re about to swing on ropes, we’re bought to learn to be children again so that we could connect again. And, that ended up being just wildly successful. The summer camp still exists today; hundreds of kids go every single summer to this camp.

There's many issues in the world, many of which I think about that I care about, but I don't waste a second of my time talking about them unless I want to do something about it. Period.

This explains everything about why community means so much to you, what your understanding of the responsibility of people and community are.

So ecology, which is both your natural environment as well as mental health, the way that people engage with each other, equity, you’re making sure that everybody has the resources that they need to get them on the right starting line. You built a place that fosters community by having the elements you pulled from learning from the Ace, elements you’ve learned from your campaign, elements you’ve learned from your time incarcerated, elements that you’ve learned from all of those things are just, human dynamics.

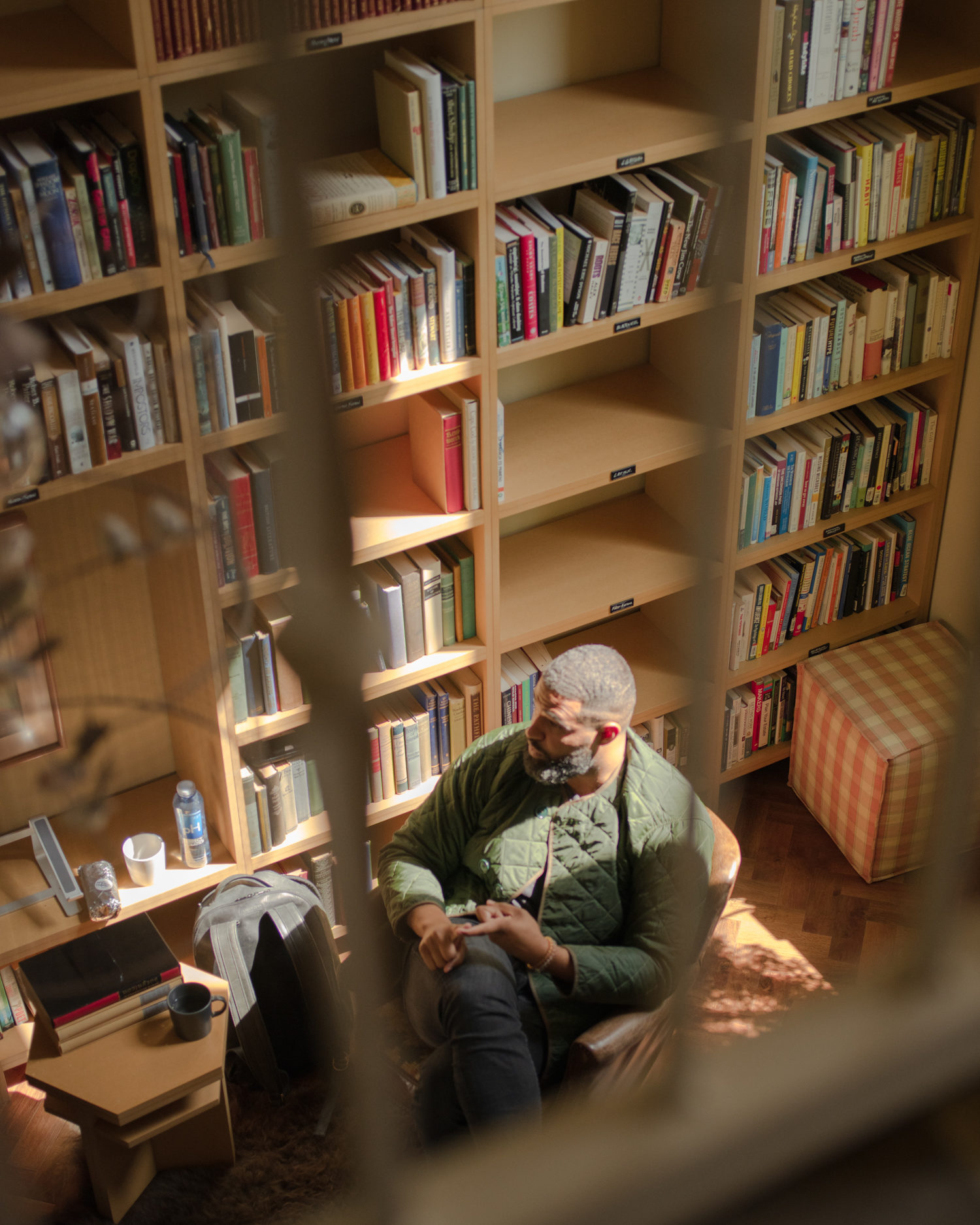

At Treehouse there are trees, there’s plant life, there’s, you know breakout spaces. We’re in the library, which is a place for introversion, but there are many other places for extraversion and activation. The current model offers a lot of value, especially for people who live alone or have small families, but do you have ideas of how this model could be expanded to accommodate larger groups of families? What does it look like for the current Treehouse model of community, to expand to larger, multi-generational families at a large scale.

We did a lot of work in thinking about this early on, and both myself and my co-founder Joe were pretty aligned on one thing. He had come out of tech and a serial entrepreneur and was successful. He had zero interest in real estate or construction. I had come out of real estate and construction. I loved it, but I had zero interest in starting to build a development company. We were both fully aligned that our product was, is and will always be community. That’s what drives us, that’s what we care about. Community will take shape in different forms; these are mere vessels that allow for the nuance of human interaction to take place more easily, and are the nuance of human need. That’s like, at the core of it.

The future of Treehouse is one where we are done throwing away our wisdom. The fact that senior homes exist in isolation makes zero sense to me.

There is an incredible amount of plant life here. What role does plant life play in giving people a sense of wholeness as a place, and why was it important to have that here?

Nature is healing, just full stop. Sitting in a barren space in Blythe, California. That’s where I was, for years. Concrete. Sand. Holes.

The consciousness of humans is shifting and starting to see that Earth matters, it really matters. Pulling from the earth, trying to actually recycle it and finding more ways to be regenerative in urban environments is important. And so that’s one part of it. The second part of it is: cooking is a big part of community.

And there’s a rooftop garden.

And there’s a rooftop garden.

And so yeah that’s plants, they’re healing. We need to go back to the dirt. We need to go back to the source of human understanding.

When we talk about the housing crisis in California, it’s the hot-take, hot-button thing for everybody. How much of the Treehouse vision was a reaction to the housing crisis?

Zero.

Zero?

The housing crisis is a philosophical crisis in this country. We have more than enough wealth, more than enough free space, more than enough apartments, more than enough apartment buildings. We do not have enough heart to let people live in them. Treehouse is trying to say, connect back to your community.

So from a philosophical standpoint, Treehouse isn’t necessarily a reaction to it, as much as an example of what can get us out of it.

Yeah.

Which is interesting because that plays into this next question, which talks about equity, and the role that the private sector can play in looking at the opportunities, the barriers to entry to things, at alleviating not just like urban housing challenges but fostering a sense of community in society. Treehouse in the private sector is doing that.

I tend to try and operate in the gray of the world [in order] to really understand things. Both are necessary, public and private. They can’t interact or coexist without one another.

The housing crisis is a philosophical crisis in this country. We have more than enough wealth, more than enough free space, more than enough apartments, more than enough apartment buildings. We do not have enough heart to let people live in them. Treehouse is trying to say, connect back to your community.

So is this a situation where the private sector can maybe lead by example to get…

We’re quicker, in the private sector.

Because there’s not as much of the red tape that you have to go through and the people that you need to appease?

Yeah, the public sector is, it’s tough, it’s complicated, it’s big. I deeply respect the politician, even the ones that aren’t great. It’s a hard job, trying to do something at a human scale. It’s a really hard job.

That’s a good point.

And turning that boat is hard.

Do you think there’s a version of the Treehouse model that could be deployed to either rehabilitate unhoused populations, whatever the case may be, in other areas of the world? Or is it more so about the principles that Treehouse stands for?

It’s the principles of why we built it. And the reason I say this is because I’m building Treehouse from the lens of a very serious Western American bias. And I’m building and I’m trying to solve problems from that context. More specifically, I’m trying to solve problems in the context of an urban environment right now. Single family homes [still] have their place. People are different there, they want to live differently. But then there are the principles of weekly dinner. Being kind to your neighbor. Being curious about their culture.

…fasting with your neighbors….

…that’s what matters. Like that’s the principles of Treehouse. And what’s interesting, it flips a little bit when you go to other parts of the world.

Right. Based on whatever baked in biases or whatever you’re pushing against…

[nods] I was in Nigeria recently. The ethos as a whole is ‘I am my brother’s keeper’. In a place of 200 million people in abject poverty I never saw a single homeless person. Period. There was a 12 o’clock curfew. We were being shuttled by security and military so we were able to see [the streets] after curfew. There aren’t homeless people.

…because everyone has the principle of…

They’re with their family. Their tribe. The wealthiest people live together. There’s no, there’s no “I got to get my single apartment”.

But Treehouse still works there. The other part of Treehouse is utilizing built space to inspire, to allow for more sort of concentrated and deep connections from a myriad of different people and not just your tribe.

That actually makes sense, because if you have the principles that are shipped, and then maybe the way it’s built is to be a template that can be augmented for wherever you are. For example, local building materials to shorten your supply chains. Maybe impacting and shifting the way that developers, urban planners look at building for community as a verb?

And if you get crazy with me, and we end up in a more human capitalistic model; the metrics by which we gauge our IRR’s today [Internal Rate of Return] will shift. Today it’s about what is our overall. The difference between our opex [operating expenses] and our revenue. That is, that is the metric that we drive things. And in that metric, that tells us to be McDonald’s. That tells us to streamline every single bit of space and how people use it. It tells us to effectively create robots. That’s what that tells us to do.

Because it’s more about the system being efficient over valuing the inefficiency that comes with being human.

Such that you could deliver a high return. And right now, our return profile is not one that values people living together for 20 years. That actually takes down opex. People getting along takes down opex. People keeping space clean, caring about where they live. Those are all things that really matter. Community happiness. There are serious benefits to a group of people being happy and sharing life together.

Treehouse isn’t the first to try this out but it’s the first to be done this way, especially being led by someone like yourself that has such baked in experience. But you’re not trying to bring people into your memories of lived experience as much as creating space for them to have one that you can learn from.

For sure. Hundred percent.

Going to the vision of what the future holds. Not everybody can live at tree house right now (because, size) but what advice would you give to people who want to build more intentional connections with the community around them, no matter where they are? And then we’ll close out by, what do you have next?

There were a few things that started to happen [last March] that were fully reminiscent of prison and South LA to me that the rest of the world thought was wildly novel. One of the most palpable were the folks singing in the apartments in Italy or singing Biggie Smalls in New York. In prison, that happened every single Friday. There were open mics, people were walked to their cells, there were sing alongs, there was poetry, the whole bit. It was the human spirit locked behind bars, locked away from one another, screaming, we want to be together.

Treehouse cannot bound the human spirit, no physical space can bound it. Then COVID hit. And we’re in a world that’s telling us to separate from one another.

One of my favorite people on this block is Eddie who lives across the street. Eddie is five feet tall and maybe 99 years old. Every single day during construction, he came and ate with the construction workers, and hung out with us. In the evening he played chess with me. Every single day. He brought his Mexican ballads that he used to listen to, brought over his record player once the cafe was built. The first time we ever sat in the cafe, and there were couches in there was with Eddie and he brought over his little record player and we listened to that. A fe days later, we finally had the AV system up and I was able to find his ballads on Apple and played them, and he danced with our team.

And when quarantine happened, I could not stop thinking about Eddie. Eddie doesn’t have family. Eddie is in an apartment by himself. Neighbors did not talk to Eddie. They didn’t talk to one another. And that’s all I kept thinking about who is looking out for Eddie. Where’s his community? Everyone’s so afraid. And I get it, getting sick and passing away, there’s consequences, they’re real. But today, we have each other, we’re optimizing for tomorrow that may not even come.

I appreciate and I believe in contextualizing ourselves as global citizens but I go back to that idea of appreciation for life and plants and clay and dirt. We are all from the earth. But we take, in my opinion, too many big swings. And we all want our names in something; we are human, we want appreciation, we want to feel validated. And the entrepreneur and tech culture of successful CEOs and unicorns and blah blah blah, it’s enticing.

Houseless people are still people. Eddie is a human being that’s left alone. Someone whose children may be crying, we don’t know if they’re being beat, we don’t know if they’re mentally challenged. There was a moment that the police were called on the parents [down the street] because they heard that the kid was yelling. Not once did someone go knock on that neighbor’s door. Did they know that person’s name? Did they ask if maybe they’re hungry?

But we’ll give to Homes for Humanity. We want to structure the biggest Deepak Chopra app to give mental healing. We’ll do all these things, but not once did someone say, “Are you okay?” “Is your kid okay?” These are the things that we take for granted. Just go meet the person next door. Small swings.

I appreciate and I believe in contextualizing ourselves as global citizens but I go back to that idea of appreciation for life and plants and clay and dirt. We are all from the earth. But we take, in my opinion, too many big swings.

There’s one common thread here which is the willingness to participate. Whether that’s participating in creating the system, whether it’s participating in dismantling the system, whether it’s just participating in questioning the system. But it’s really about participating in proximity with people, as opposed to our self imposed isolations or ideations of, “oh you know I’m gonna figure this out on my own”. And you’ve created a wonderful space for people to experiment with what that looks like. So what’s next.

The dream is to have a Treehouse in every single corner of this world. I hope that Treehouse is a part of impacting the overall zeitgeist. The American dream has been centered around the single family home and all it’s accoutrements, which played into the market. If you and 100 million others can buy a vacuum, that is a big market. Versus, having one vacuum for the whole building, or for the whole community.

I’m not saying single family homes are inherently bad. There’s a lot to learn from a single family home. And that’s the dynamic of the family. Our next big building is three times the size [of the Treehouse Hollywood location]. The first floor is a local market with a multitude of local vendors and then the next two floors are just for families. I lived here with my daughter, there’s serious stuff that a family still needs to accommodate. There are private moments. There are moments of serendipity that have to happen through the family to make sure those bonds are cared for. There are moments of vulnerability that need to be designed for.

As opposed to still designing for just the single person.

Right. And so in that building, you have more two bedrooms and three bedrooms that are more quaint for the family and they open off into a courtyard because, what do we want people to do? We want them to be free. So that courtyard has a playground dedicated to the children. And the adults don’t have to feel afraid for their kid to play outside, in a major city. Above that there are a variation of micro studios, one bedrooms, and two bedrooms, 50% of which is affordable. I’m excited for older generations to move in.

What would that look like for people who aren’t working, coupled with the full playground and daycare space? I’m done talking to Washington about early childhood education.

You’re just going to show it.

We’re just going to do it. The top floor and the roof is a private club. Why? Because you don’t have to deny human vanity and things that people care about, like good design.

…just include it in the conversation.

…just include it. But with that private club we’re going to make a statement: that it’s for the people who live in this area. Obviously the rest of Los Angeles is invited, but…

It’s local to where it’s local to.

It’s local to the community. In LA alone, we’re trying to get 12 of these in backlog by the end of the year. COVID happened, but I dream of the day that this building is a catalyst for the entire neighborhood.

Last thought and story, Geoffrey Canada. Harlem Children’s Zone. My biggest hero. [He] had an idea. And he said, on this block in Harlem, on this one block (not the big swing) but on this one block every kid will be able to go to college, if that’s their decision. Every mother will be able to live in the hope and sacrifice that she’s made, every father will be made whole again. It’s ugly down the street, we’re going to plant trees. Ownership matters. We’re eventually going to be able to buy all of this. 97 blocks later and hundreds of millions dollars later, they were purchasing housing projects entirely from the government and upgrading them. 100% high school graduation rate later. 97% college graduation rate. Brilliant.

That’s a North Star if there ever was one. And we want this to be a catalyst for more.

I want it to be more. And I want Treehouse to impact the vision of the American dream as one that values interdependence. Right now, we value independence too much.

I’m stopping that there, for so many reasons.

—

This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

To find Prophet and Treehouse:

@prophet_walker

@treehousecolive

treehouse.community

Next Story

Discovery, Issue 01