If 2020 was the year of the virus, and of staying at home, then 2021 has to be the year of re-emergence; the year we break free from the cocoon of yesterday that has for too long been scripting our future for us. In 2020 we looked to scientists for answers, we protested to governments around the world asking them for reform on age-old inequalities, and we looked to each other for friendship and support. Could 2021 be the year we look to designers to help imagine and build a better future? What role can they play in rewriting the script of tomorrow?

As a species, Homo sapiens are anomalies for countless reasons; our cognitive abilities, our imagination, and our ability to inhabit the planet in such large complex social groups. But perhaps the most evident of all is that, despite our evolutionary past, we have gradually and steadily grown further away from the force that shaped who we are – nature. Since the earliest microorganisms appeared on Earth, nature has been testing, observing, and refining every living thing to create a singular functioning ecosystem. However, in the mid-18th-century humanity went through its third metamorphosis – the industrial revolution. With new tools and machines we discovered how to cheat nature, we discovered ways to create new materials, speed up processes, and ways to build what nature couldn’t. Since then our dependence on infrastructure, the global supply chain, and technology has left us with little opportunity to question the sustainability of those practices and all that they create – until now. 2021 is the opportunity we didn’t know we needed.

I can remember the first day of design school like it was only last week. The building we were studying in had high windows, so that the light pooled in across the ceiling. The space was divided into three areas by tall partitioning screens, and punctuated by a handful of concrete pillars. It wasn’t beautiful, but it became home. I stood with my back against one of the partitions, anxiously watching as the course leader goes around the room asking each of my classmates why they wanted to be graphic designers, and what kind of work they wanted to create. When it’s my turn to speak, I pause; what is graphic design? What do graphic designers do? To this point I’d only ever walked the line between photography and fine art, never really fitting comfortably into either camp. My answer was disappointingly average, barely warranting a response. A decade later “why graphic design?” and “what do you want to create?” are questions I still ask myself, and the truth is that my answer evolves. Since graduating I’ve worked for a handful of agencies, producing work for all manner of clients – from visual identities for startups, to billboards in Times Square – but the motivation behind all of that work is always to create something that transcends just aesthetic beauty, and adds lasting value to people’s lives. As to the why of graphic design, the answer I most commonly arrive at is the belief that, through design and visual communication, I can leave the world a better place than the one I was born into. My definition of ‘better’ changes depending on the project, but increasingly it has come to mean work that is more thoughtful, inclusive and conscious. Thinking back to that moment on the first day of design school, I was blissfully unaware of the responsibility that being a designer carries with it. Design touches almost every aspect of our lives, from the cars we drive to the houses we live in, and from the clothes we wear to the companies we choose to buy them from. For me, the realization and acceptance of that responsibility marked a significant shift in my perspective – if I was going to have such an impact on the world around me, then I had to hold myself accountable for the conditions that I was creating.

Responsible design has to become a question of ethics that designers are continually asking themselves. In other words, if design is not responsible or sustainable, can it be beautiful?

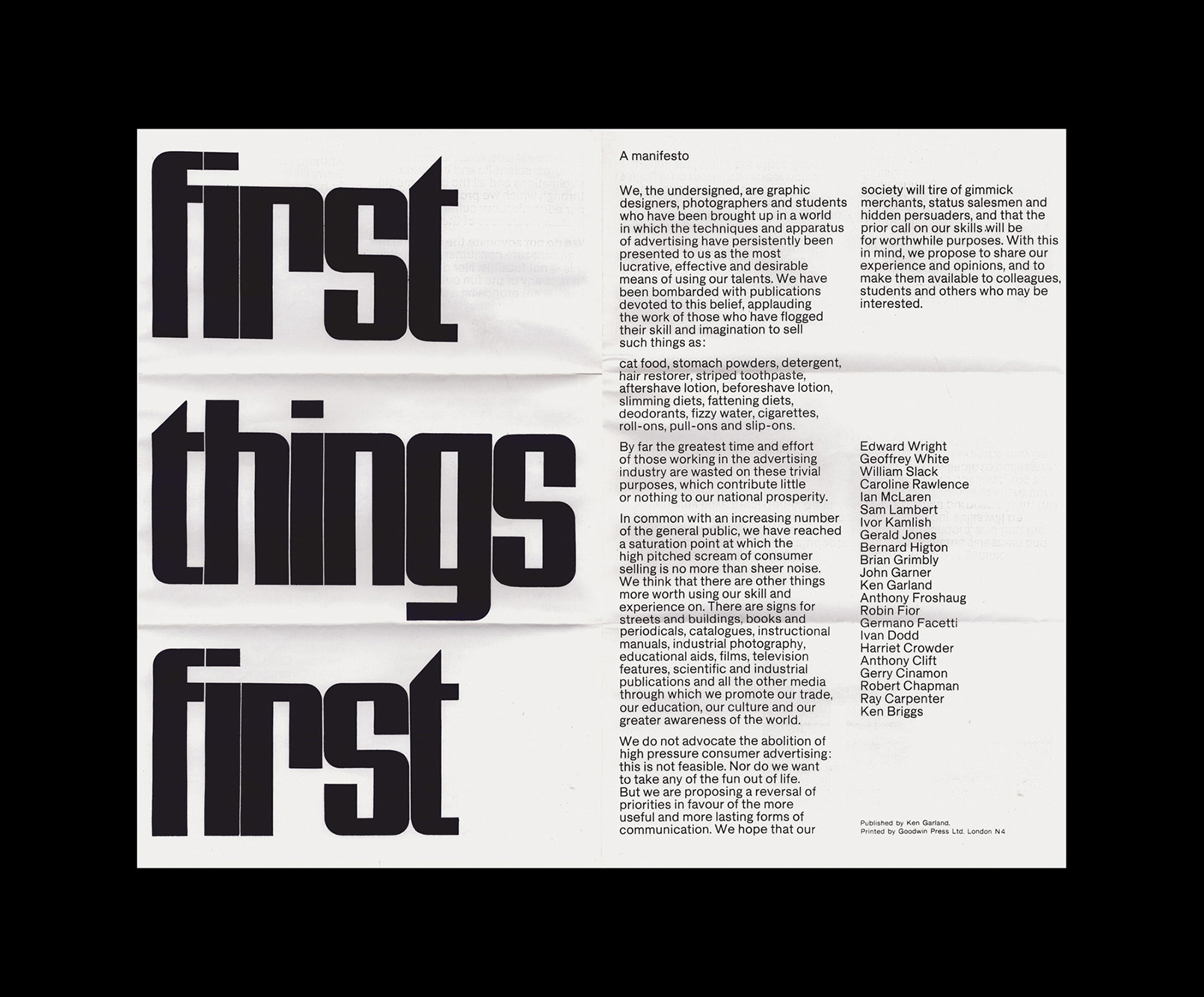

Responsible design is not a new concept. In 1964 British designer Ken Garland published the “First Things First” manifesto that called on creatives to recognize the “high pitched scream of consumer selling”, i.e. advertising, is nothing more than “sheer noise”. The manifesto professes that designers have a responsibility to society to use their talents and experience to “promote our trade, our education, our culture and our greater awareness of the world”. In more recent years, the notion of responsible, or ‘sustainable’ design has gained momentum among both small businesses and large-scale enterprises. However, its implementation is still too often directed by the client rather than the designer. In order to see a real, fundamental change in the way that our future is designed, responsible design can no longer be seen as an optional directive, a box to tick. Responsible design has to become a question of ethics that designers are continually asking themselves. In other words, if design is not responsible or sustainable, can it be beautiful?

Perhaps we have reached a turning point in the way that we perceive design, one where neither form nor function comes first but instead, they are perfectly aligned. Have we moved past the age of aesthetics in favor of creative solutions that don’t just look good, but also do good for people and the planet?

The relationship between nature and design is one of opposition, where organic meets synthetic, grown meets built, and science meets art. The climate crisis and myriad other environmental challenges we face have, perhaps reasonably so, led to the belief that whenever humanity and nature mix, there can only be one winner; either nature is exploited for the benefit of humanity – think fossil fuels and agriculture – or it is protected, but at great expense. However, as we look towards a better, more responsibly designed future, we need to start looking at the relationship between design and nature as a kind of symbiosis where each benefits the other. A shining example of nature and design coexisting can already be seen in Copenhagen, at the Amager Resource Centre designed by the Bjarke Ingels Group. The resource center, commonly known as CopenHill, is a waste-to-energy plant on the Danish island of Amager. Although the generation of clean electricity is the plants primary function, its architecture also serves as a rooftop ski slope, climbing wall, hiking trail, and a haven for nature. What is on the surface a very necessary piece of modern-day infrastructure has, through responsible design practice, been able to demonstrate positive social and environmental impacts, both while maintaining and growing its economic viability.

CopenHill is undoubtedly a new benchmark for modern infrastructure, but the design of the future has to exist not just on a macro level, but also on a micro level. In order to reimagine our future habitats, we must explore progressive systemic changes while simultaneously obsessing over the every day; challenging the current paradigm of what responsible design means to the individual. On a macro level, we can think of responsible design simply as large-scale projects with positive social and environmental consequences for the wider community, both locally and globally. Conversely, responsible design on a micro level has to do with the influence that design can have on us, as individuals, and on our daily routines. Where we live and how we live are the building blocks of society and culture. The clothes we wear, the toiletries we use, and the cars we drive are all designed but, until only recently, how they’re designed and produced has been undeniably human-centered – that is, with the sole purpose of benefiting humanity. To design our way to a better future, we must first create the opportunity for change on a micro level, because it is these adjustments that will ultimately help to inspire change on a wider scale.

In April 2019, UK brand Bottletop launched the TogetherBand campaign to support the UNs 17 global goals for sustainability. However, the campaign goes beyond just selling bracelets to raise money; innovative design and manufacturing mean that the signature ring pull clasp can be made from seized illegal firearms, while the band itself is made from plastic waste that is pulled from our oceans. Similarly, sustainable apparel brand Pangaia recently launched a collaboration with Air Ink, creating responsibly crafted garments printed with ink made from captured carbon emissions. Responsible design, on a micro level, allows Bottletop and Pangaia to create a positive social and environmental impact, while educating the consumer, contributing to a larger goal, and remaining economically viable.

©Bottletop TogetherBand

Pangaia X AIRINK®

In my own practice, responsible design starts with a set of values; born out of the desire to be more thoughtful, inclusive, and conscious. As a discipline, graphic design is perhaps more likely to be associated with micro-level changes than it is the macro, largely because of its intimate relationship with the individual. The art of visual communication will be vital in our future; it will influence the way that we receive and digest information, the way that we perceive the world around us and the way that we communicate with one another. For me it’s the micro-level touchpoints and interactions that we all experience everyday that provide the greatest opportunity for graphic design to play it’s part in creating a better future. Whether it’s finding new, compostable substrates for packaging and printed materials, or understanding the energy efficiency and carbon footprint of a light background on a website compared with a dark one; the potential for change is vast and exists at every stage of the design process – from ideation right through to execution. When I think about the future relationship between nature and design, and the responsibility that designers have to our planet, it is clear to me that change has to begin with education, for how do we begin to design solutions to problems that we cannot comprehend? Only once we properly understand the challenges that we face, can we unite in the singular vision and endeavour towards a more responsibly designed future.

Our future will undoubtedly look much different to the world we see in front of us now, the question is whether or not we can do what must be done today to secure a better tomorrow. Designers have an important role to play in the coming years; on their shoulders the heavy burden of providing responsible, sustainable and economically viable solutions to complex problems. While the task of reimagining our own future living conditions will be significant, there is another equally important role that designers must fulfil. As we design and build we must also nurture and grow; we need to see beyond our own impact and help to inspire others, fostering innovation, creativity and accountability in the next generation of designers. 2021 has to be the year that we re-emerge; more conscious in our practice, more demanding of our industry and more passionate in our endeavour. Our future habitat will be decided by what we do here and now, the script is ready to be rewritten, we just have to pick up the pen.

—

To find Joe:

@wearetitle

View More:

- Issue 01,

- Design ,

- Habitat ,

- Sustainability

Next Story

Interview, Issue 01

Community is a Verb with Prophet Walker

The visionary redefining the the relationship between community and shelter.

Read Story