British Architect Norman Foster, known for his modernist high-tech architecture and early adoption of energy efficient construction techniques, once said, “Architecture is an expression of values.” It’s a straightforward supposition that the values of a society should be reflected in its built environment, which shapes how we live in very tangible ways. Inspired by this prompt, we took a look around our own built environment, which happens to be the city of Los Angeles, and wondered what values it reflected. It’s no secret that the city we live in, and in a larger sense the state of California, is facing challenges that are very much intertwined with the subject of its built environment: approximately 57,000 people within the county limits are unhoused on any given night, and the city itself has a current deficit of 500,000 affordable housing units.

There are plenty of challenges facing modern American cities today: crime, transportation, infrastructure, education, affordable medical services, amongst others. But the most primary current need is housing, which we’d argue is the foundation to any economically and socially sane city. It’s fundamental for citizens to have safe places to live; if people can’t afford homes in the city they work in (in our case Los Angeles) or aren’t reasonably able to place themselves on a path to homeownership, people, in other words workforces, will eventually be forced to flee. And a city cannot survive without workforces across all economic strata. Smartly densified housing that promotes social cohesion is key, first and foremost; solving for the other challenges can then build upon that foundation.

We therefore posited that shelter should be a fundamental human right and sought to demonstrate how good design could be deployed to realize such a vision. We could’ve never predicted how contentious, and deeply layered and complex, the subject of housing would be. And as any curious minds would, we decided to embark on a journey to unpack these new-to-us layers and are now in the throes of an ongoing attempt to bring ourselves to full consciousness on the subject.

Not merely a collection of individuals sharing a sprawling urban landscape, but communities that can come together, learn from one another, exchange, grow; to make life better for each other. Many of these shifts are already underway, with a focus on knitting the city together in reimagined ways: an expansion of the city’s limited subway system, addressing the housing crisis with calls for higher density, and the creation of more public spaces, to name a few.

Los Angeles

One of us grew up in the San Fernando Valley, just north of the city, and the other spent many formative years here. Los Angeles’ sprawl – its vast distances between destinations – and the subsequent time sacrificed to freeway travel were all just givens. But if you’re not from Los Angeles, experiencing it for the first time can be shocking. Gazing through the airplane window during his first descent over Los Angeles in 1973, Dutch writer Ceese Nooteboom saw “houses from horizon to horizon”. He spent the next few weeks walking the boulevards, driving the freeways, taking the bus from one end of Los Angeles to the other, looking for a center that would validate his European sense of what a city should be, but couldn’t locate one. Many cultural commentators have designated the city in a similar manner. Its immense physical scale plays a role: five hundred square miles and counting. In its early days, Los Angeles provided a sense of limitless possibility that encouraged people to develop further and further to and beyond its edges. This rapid urbanization resulted in a city with not one center but many: Downtown, Koreatown, Little Tokyo, Century City, Hollywood, Silver Lake, Westwood, Venice, and so on. LA is also, confusingly, a city within the County of Los Angeles; the County comprises 88 cities, including LA, Beverly Hills, Santa Monica, Culver City and West Hollywood, each with their own civic government.

Even more confusingly, “LA” is also loosely used to refer to a five county region, made up of Los Angeles County, along with Orange, Riverside, San Bernardino and Ventura counties. The former Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne has characterized this Los Angeles not as just one but as three. For Hawthorne, the first Los Angeles existed from 1880 to World War II, and was given its character by a housing boom that followed the West’s railroad expansion across the vast Southland. The second Los Angeles occurred from World War II to 2000 and was driven by an outward growth as the city’s urban development focused on a lifestyle of privatization in order to accommodate the car and the single-family home, resulting in a city that is more or less a collection of houses with decentralized commercial hubs. The third Los Angeles is now and the one we are working towards, in which mass transit, associated with the first LA, and denser housing is overlaid on the second LA. In the third LA, the architecture journalist Frances Anderton sees a curious pattern of housing development: carpets of single family houses, mid-sized subsidized and market rate multifamily on arterial routes and luxury towers in central business districts like DTLA. None of these offer accessible housing for the middle income resident that makes up the workforce in Los Angeles.

The value of interconnection seems crucial here, and in practice could be many things. Breaking down social barriers that have isolated certain groups of people from others, and relegated many opportunities for upward mobility to a select few would be one. Another would be recognizing the psychological value of living within a community; that as social creatures we’re not built to endure the isolation incurred to achieve certain aspirational standards. A third would perhaps be exploring shared cultural identity; what values make Los Angeles, Los Angeles? Not merely a collection of individuals sharing a sprawling urban landscape, but communities that can come together, learn from one another, exchange, grow; to make life better for each other. Many of these shifts are already underway, with a focus on knitting the city together in reimagined ways: an expansion of the city’s limited subway system, addressing the housing crisis with calls for higher density, and the creation of more public spaces, to name a few. A tall order, and one that places a heavy burden on architects to help us visualize these changes. But this responsibility cannot be borne entirely by a single discipline, nor simply look to building better environments as the sole prescription. Reimagining a city takes a village, and Los Angeles’ current village is composed of some inspired and inspiring individuals.

How Policy & Economy Are Intertwined

In order to build better environments, one must first, and very fundamentally, have a deep understanding of the way our cities are planned and zoned. This informs how the law and the interests it is beholden to shapes the way its citizens live. Los Angeles isn’t necessarily unique in its zoning laws; seventy-five percent of residential land in many American cities is devoted to single-family homes. In Los Angeles that number is 80 percent. But because it is the second-highest populated city in the country behind New York City (of which only 15 percent of its residential land is protected for single-family structures), it has made its way to the very forefront of a density reckoning that the majority of the country will at some point need to face. For Angela Brooks, architect and Co-Principal of Brooks + Scarpa, the ratio of zoning in Los Angeles (80 percent single family, 20 percent everything else) needs to be flipped. “What people don’t realize is that it’s been so difficult to build these days as architects. We have so many competing forces, but ultimately the zoning code is dysfunctional,” said Brooks. “People talk about gentle density. I’m through with saying it’s gentle. I think we should say it’s radical. We need to do a radical reorganizing of what we’re doing in the city.”

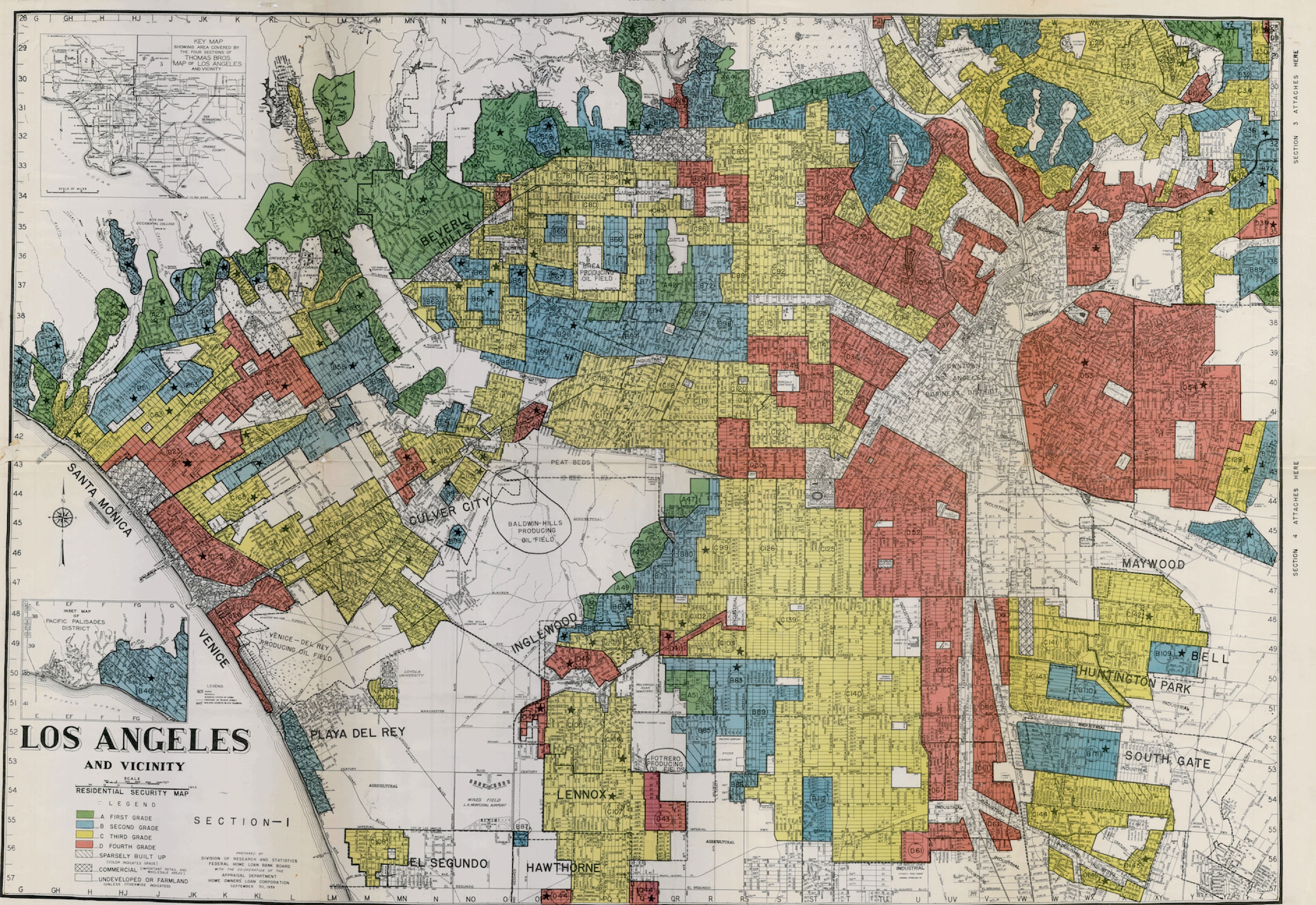

Economists also view the type of restructuring that Brooks is calling for necessary to alleviate the growing strain on housing affordability. Other groups, such as environmentalists, view it as a means of reducing gridlocks that lead to transportation emissions. Activists concerned with social justice reform see it as a key to opening access points and opportunities that have otherwise been denied to certain populations. As with other American cities, during Los Angeles’ era of massive urban development the Home Owners Loan Corporation (HOLC) published worksheets rating individual neighborhoods in Los Angeles as security risks for home loans. The highest rating was green (A), followed by blue (B), yellow (C) and finally red (D), which introduced redlining into the vernacular of federal home financing. Often the HOLC’s redlining maps reflected the racial geography of the city during this time: African American, Mexican American and poor white neighborhoods received red and yellow ratings while middle- and upper-class Anglo neighborhoods received a green or blue designation. The long-standing effects of these practices can still be felt today, where the rates of homeownership are drastically lower in redlined communities than in neighborhoods which received higher ratings.

In a recently published book, Urban Magic: Vibrant Black and Brown Communities are Possible, Los Angeles-based architect Michael Anderson calls for what he’s coined as “Accelerated Equity Housing,” a proposed program that aims to align the interests of public funding, private capital, and real estate developers to rapidly generate wealth in these historically neglected communities. “It specifically targets Black and Brown families to come back as first time buyers,” Michael told us over a Zoom call in June. Anderson is lobbying for first time buyers to receive federal subsidies that would enable them to purchase triplexes and fourplexes in transit oriented communities. The development of these transit oriented communities, or TOCs, is an effort by LA Metro to implement policies that maximize access to transit as a key organizing principle in land use planning and community development. Anderson’s proposal is unique relative to other affordable housing initiatives in that it addresses homeownership and the long-term value in generating wealth in these neighborhoods.

Michael Anderson's recently published book, "Urban Magic: Vibrant Black and Brown Communities Are Possible".

“It’s growing the economy of the average household incomes, but also making it possible for the younger generation to come back,” said Anderson. “They’re going to bring their lifestyle to the community, and that’s what’ll raise the activities along the commercial corridors. To me this is a way for existing mom and pop businesses to also have the benefits of the younger generation coming in to make it a cool place.”

A Different Perspective on Density

Anderson’s “cool factor” is an important point to address. Asking ourselves what makes a city aspirational or desirable is also a necessary building block on the road to achieving many of the goals held by modern American cities. Most cities have their thing that makes it desirable; Los Angeles’ thing is an expansive, sunny, easy-going lifestyle. Its history of low-rise structures to facilitate a year-round indoor-outdoor style of living is, for most, a worthwhile trade off to the negative aspects generated by its vast urban sprawl. Historically, and even today, the aspirational home for the Angeleno is not a condo in even the swankiest of high rises as is considered highly desirable in a city like New York. It’s a sprawling house in the hills, or at the very least a stand-alone home with ample yard space. It’s a city that has proved itself culturally allergic to residential density which many argue it needs to embrace.

Luckily culture evolves and can adapt to meet the goals of new eras. If our psychology is most change-averse when confronting unknown frontiers, once we can imagine a change and tangibly visualize its benefits, it’s easier for us to shift our perceptions. Showing people what could be is a task often best executed by designers, the ones who help us imagine new and different worlds. “I think architects and urban designers have a unique set of skills and tools to help people visualize what density can really mean,” Christopher Roach, a San Francisco-based architect and urbanist, shared with us. “Density can come in many forms.”

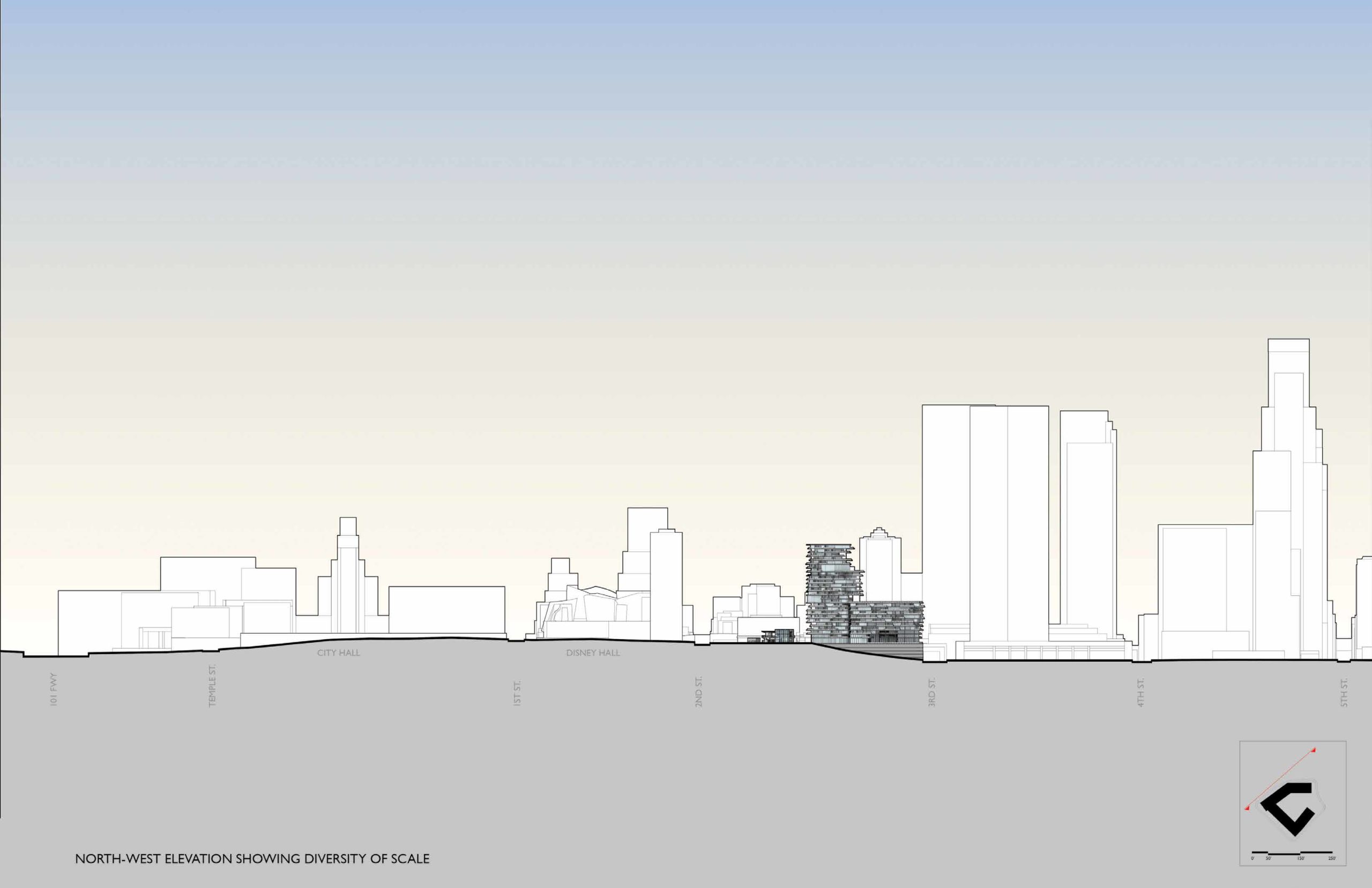

So what could aspirational density look like in Los Angeles? The architecture firm City Design Studio is in the pre-development stage of a fairly ambitious project: a transit-oriented, mixed-use residential tower in the heart of downtown that aims to realize private indoor-outdoor living at its 20-something stories, completely maximizing its downtown views. “We wanted to try and find a way of creating something that is unique and will also offer the ability to live above the city, even if you aren’t living up on the hill,” said Farooq Ameen, the Principal of City Design Studio leading the project. The tower will sit on a major transit hub, connecting residents to every Metro line in the city and offering an alternative vision of what an aspirational home may look like to its citizenry. While the project won’t solve the residential inventory and affordability issues that low-to-middle earners are facing, it could potentially evolve the city’s imagination into one that holds a certain level of pride for its higher-density structures and eventually help loosen its grip on a reverence for the single-family home.

City Design Studio's Panorama Project

City Design Studio's Panorama Project

A Culture of Interconnectivity

Recognizing interconnectivity as a value also requires assessing and addressing how people on all strata of the socio-economic ladder relate to one another.

It’s no secret that housing affordability is a pressure point in Los Angeles, and California more generally, where the real estate market has spent the past couple decades climbing sharply without any signs of slacking. The resulting strain is perhaps no more apparent in any corner of the city than in that of Venice, which has seen rapid gentrification in recent years. Venice’s demographics of 20 years ago are virtually unrecognizable today; prior to the neighborhood’s transformation into an enclave for the tech bourgeoisie, it was a beach town that was home to beatniks, artists and working-class Black, brown and white residents and people living on the street (whose numbers have escalated in recent years). Those who loved and appreciated the earlier Venice criticize its current cultural hegemony.

For Eric Owen Moss, the neighborhood has a wonderful pedigree. Moss is the renowned architect leading the design of the recently approved Reese Davidson Community, which will bring 140 apartments for formerly homeless, low-income residents and local artists to Venice along with storefronts including a cafe, a theater, a revitalized canal with improved public access and a parking structure with double the spaces than the surface lot that occupies the property today. While the project has already been approved, many local residents oppose the new addition, citing critiques on its brutal-esque design, fears of increased crime, an impact on neighborhood character and home value decline. Some residents that have paid millions for their properties in Venice, and have to pay steep taxes attached to those home values, have called into question the fairness of the Reese Davidson Community’s future tenants’ ability to receive subsidized housing on a parcel of such prime and pricey real estate.

Moss appears unphased by the criticism, likely due to a sense of urgency toward the acute housing challenges that the area is facing. “It’s an honor and a privilege to work on the kind of project that we’ve always claimed we can do,” commented Moss on a panel organized in conjunction with the pop-up exhibition Low Rise, Mid Rise, High Rise: Housing in LA Today, co-organized by Frances Anderton. Despite being one of the nation’s buzziest neighborhoods, Venice hasn’t increased its housing capacity in 15 years. In fact, the neighborhood had roughly 700 fewer housing units in 2015 than it did in 2000. A stall in apartment development coupled with a trend of affluent homeowners acquiring adjacent properties and leveling them to gain more space have been contributing factors. And on top of it all, approximately 12 percent of the neighborhood’s housing units are tied up as Airbnb listings. The reality can no longer be ignored: it’s estimated that Venice is now “home” to 2,000 unhoused people across its three square miles.

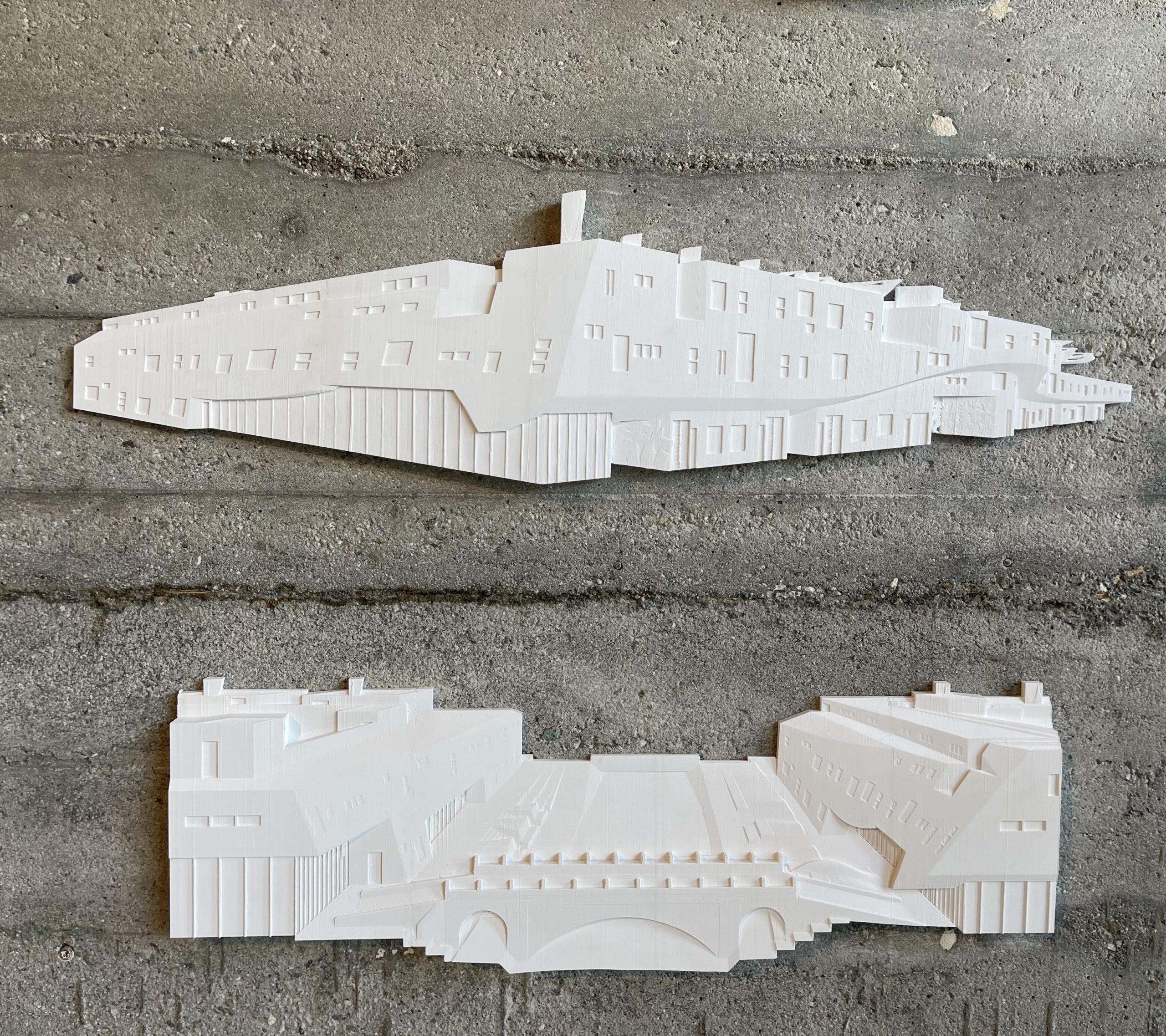

Relief of the planned Reese Davidson Community by Eric Owen Moss Architects at Low Rise, Mid Rise, High Rise: Housing in LA Today.

Digital rendering of the Reese Davidson Community.

The contention around this project prompts fundamental questions: who is a neighborhood like Venice meant to serve anymore? And on a larger scale, who are our cities meant to serve? In other words, who and what do we value? The expression of these values ebb, flow and morph over time, and as a result the man-made world around us changes. Sometimes the change happens alongside us – the citizenry or larger community – and sometimes it happens despite us, serving the interests of a certain few. But either way our behaviors are shaped by the interactions we have with that built environment. A structure can’t be a living thing, per se, but it can encourage or disincentivize behavioral patterns amongst each other, both positive and not so positive. In this sense, the virtues we embed into the buildings we create mean something. They matter.

Architecture needs to consider political, social, financial and environmental factors to be functional and relevant for decades, even centuries, to come. A collection of houses can be just that, a collection of houses. Or that collection of houses can be a community. A high rise can be a solution to density, or it can be a vehicle that nudges a city toward renewed ways of living and interacting. An affordable housing project can not only provide shelter for those who need it most but also force a conversation on growing wealth inequality. Urban ecosystems mirror that of natural ones; one cannot know a part without understanding the whole.

View More:

- Issue 01,

- Architecture ,

- Los Angeles

Next Story

Interview, Issue 01

Chef Phuong Tran: Rooted in Creativity

Chef Phuong Tran, of Croft Alley in Los Angeles on cultivating connection.

Read Story