Part reaction to the over-digitization of our lives, and part instinct, Chef Phuong Tran of Croft Alley in Los Angeles wanted to cultivate community through the medium of a cafe that felt like home.

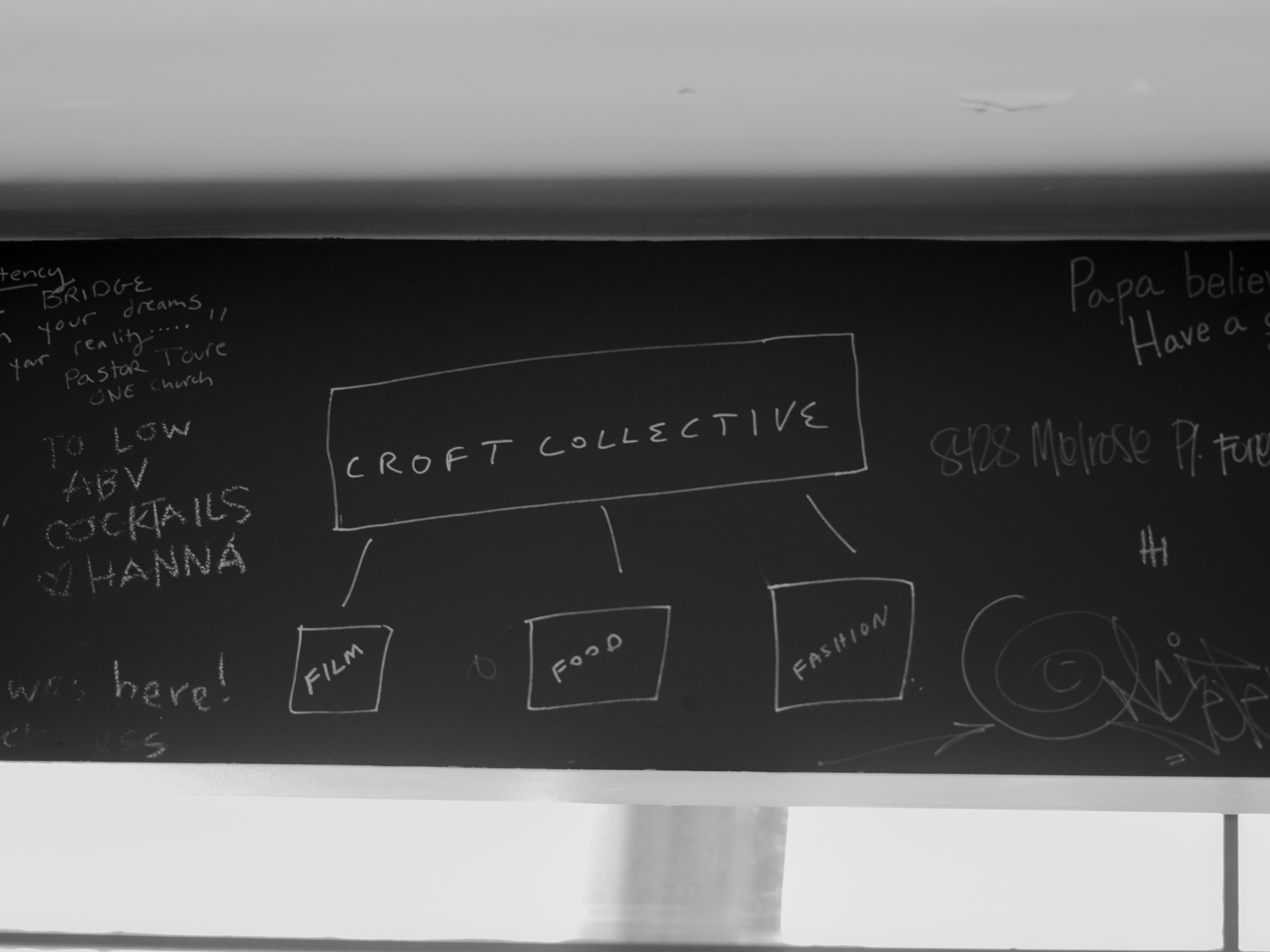

Phuong Tran plays by his own rules. He opened his restaurant in an alley, almost hidden away, in a city that often prefers flash to subtlety. They didn’t do press, and for many years the restaurant rarely posted to its Instagram account. Much of the seating in his restaurant is communal but in a way that doesn’t try to play into a dining experiment or fad of the current generational sort. He is an incessant observer; a note-taker, a people watcher. “What I’ve noticed about the different cities I’ve lived in isn’t about the architecture or the art but about the people. I think that’s what’s the most valuable part, watching people’s behavior,” he told us. His curiosity in people and culture is taking him on creative journeys beyond the culinary; he’s soon to launch an apparel project and a book of his compiled illustrative notes that serve as the foundation for his recipe concepting. We sat down with Phuong on a Monday morning in the original Melrose Place location of his restaurant, Croft Alley.

On creativity.

Looking at all the disciplines one studies, I’ve realized that most figureheads, world economic leaders for example, should be able to predict a recession. But they only tell us what happens after it happens. Medicine only tells you what’s happened to you after it’s happened to you. My background is in physics, which only explains things after it’s happened, after it’s been observable. I’ve realized that these fields are all reactions to life. But the ones who create new worlds, imagine the ways things could be, are in the creative world.

On the American immigrant experience.

There’s a distinction between immigrants and refugees. You’re a refugee if you’re from a war torn country, which was the reality in my case. It wasn’t a choice my family made. In my case, families were facing death, they were facing the North Vietnamese coming down. And fathers were also facing death. So I look at my experience (I was very young, five or six), uprooted into a strange setting. We first landed in New Orleans. I couldn’t recognize what home was anymore, so home just basically became where we were.

My father would really force English on us while my mother was still trying to teach us Vietnamese, and making Vietnamese food. So there was this huge dichotomy between both worlds happening. Growing up I had to really focus on my language skills. I worked hard just to fit in. By the sixth grade I won the spelling bee. But I never really felt I achieved, or really “fit in”. So I don’t think there has been any complete reconciling, but nor do I think I have any of that reconciling to do. I think it’s a lot more about acceptance of your circumstances and making do of it. I suppose that’s the real reconciliation of it all. Home is really where you create it. I think it’s mostly mental.

On making decisions.

I’ve mainly honed my decision making process from learning what I don’t like, or what I don’t want to do. That played a role in how I did my business, but also how I operate in my life. When opening a restaurant, the questions you get are: who is your designer? Where are you located? Who is doing your PR? The food I was doing was almost irrelevant. I thought that was the wrong thing. The wrong way of looking at it.

At the same time social media is telling us what to wear, what to eat, where to go. I thought there was a certain sense of individualism missing. So I’ve really approached this experience, and other projects I’m working on, from that lens. Maybe as a reaction to what I see around me, recognizing what the wrong thing is. And creating solutions to remedy that.

On neighborhood and community.

I always wanted to build my own ecosystem. I believed there was a percentage of us that weren’t just looking for four walls and a door, where you have to download an app and make a reservation to come. Or food with a big ego. I wanted people to just come in. The culinary arts, unlike other art forms, is very ephemeral. We only have that moment with the client or the diner for five minutes or ten minutes, however long it takes for them to finish that dish. Then your art is gone. Musicians, their songs can live on. A Nirvana, a Bob Dylan song, those transcend time. So when I started this, I asked myself, am I doing pop, which is only that moment? Or am I trying to create a bigger impression? How do I make a deeper impression long after you’ve left?

On inspiration.

I’m constantly listening to music. The Radiooooo app is great for discovering music from around the world across different times and for understanding culture.

Also through a lot of travel. I worked on a permaculture farm in Columbia a few years ago. The government was converting a lot of the land recovered from cocaine dealers so they allowed some people to come and work on it. My business partner and I landed and were there for two weeks. We stayed on the farm, lived with the farmer. He has a typical farm, which has all of the typical animals that you normally see on farms, but also has wolves that live just outside the property. At first he had an issue with them eating his chickens. But what did he do? He fed the wolf. I asked him why he’d do that. His response was, “We all have to live here. And they have to eat”. I thought that that simple solution was everything. I draw a lot of inspiration from people like him.

On books and films.

Babette’s Feast (film) and The Death and Life of Great American Cities (book).

One last anecdote on the topic of the book recommendation. There have been a lot of studies where researchers would give rats, isolated from any sort of community in a cage, the option to drink regular water or water with drugs. Cocaine. The rats would go for the drugged water and essentially just drink themselves to death. In the 70s, a researcher came along named Dr. Bruce Alexander with an experiment he called “Rat Park”. The rats had everything they could want in their rat park: they were free to roam and play, they had companions to socialize with, and they had the same option of the two waters. But in the rat park the rats never go for the drug.

Built environment, community is so important. We’re dealing with addiction in a wrong way. We’ve been dealing with addiction as a compulsion. He was saying, no, it’s not a compulsion. The opposite of addiction is connection.

—

To find Phuong and Croft Alley:

@chefphuongtran

@croftalley

croftalley.com

View More:

- Issue 01,

- Culture ,

- Food ,

- Los Angeles

Next Story

In Practice, Issue 01

Exploring Tactility through Urban Farming

San Diego-based hairstylist Rachel Duhame became a farmer this year. Her perspective on leaps-of-...

Read Story