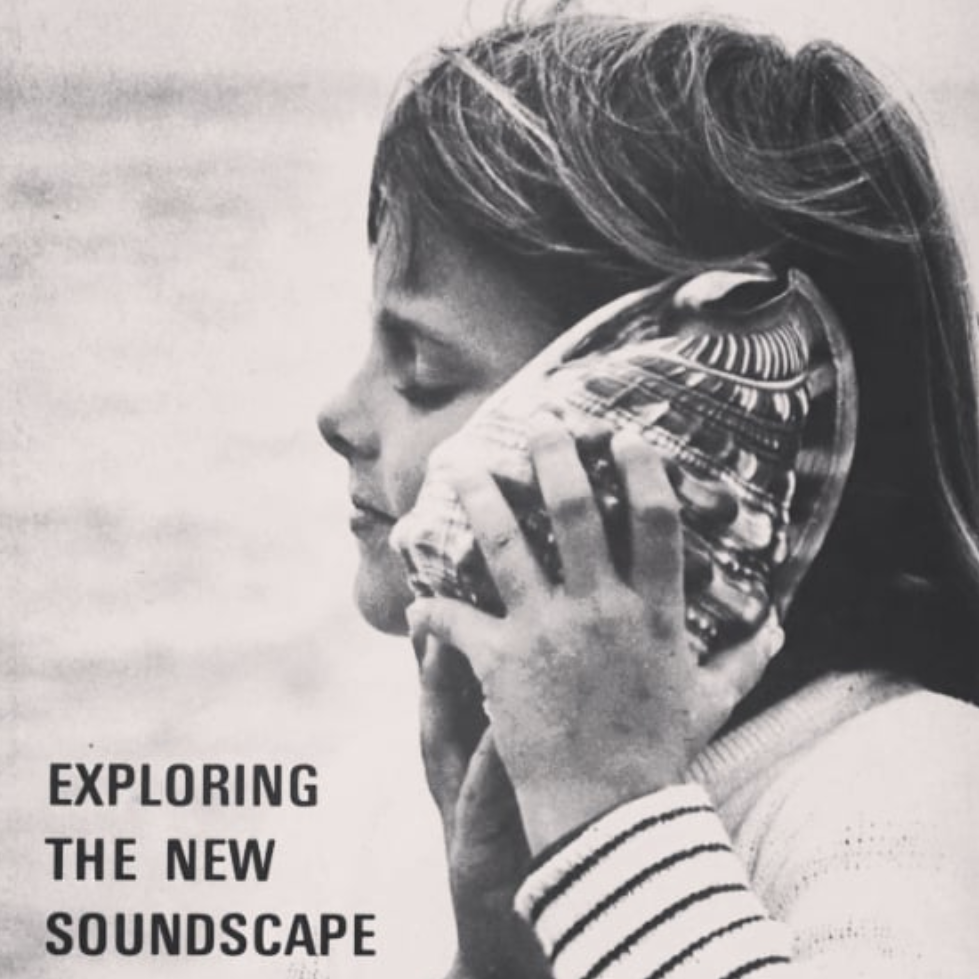

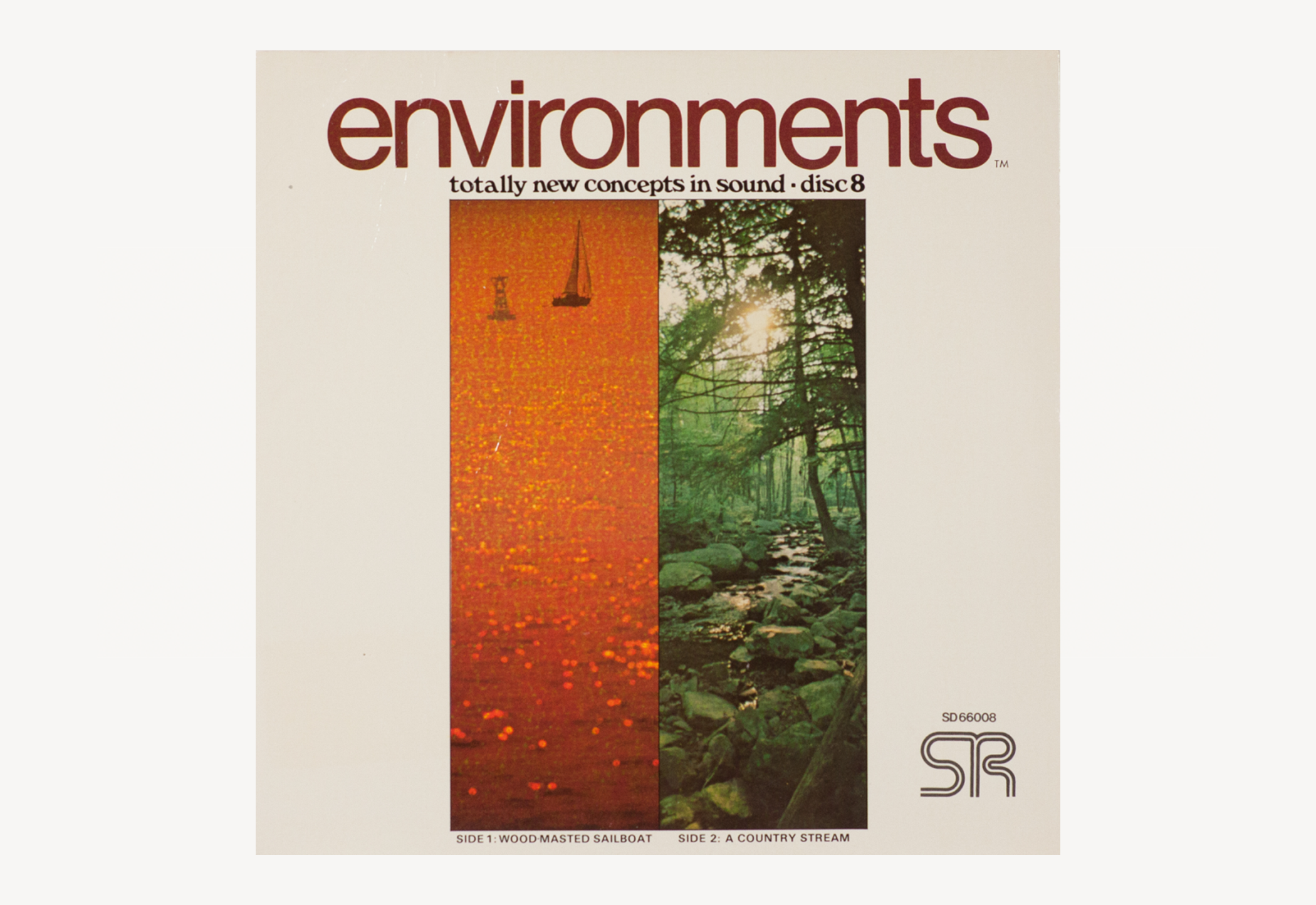

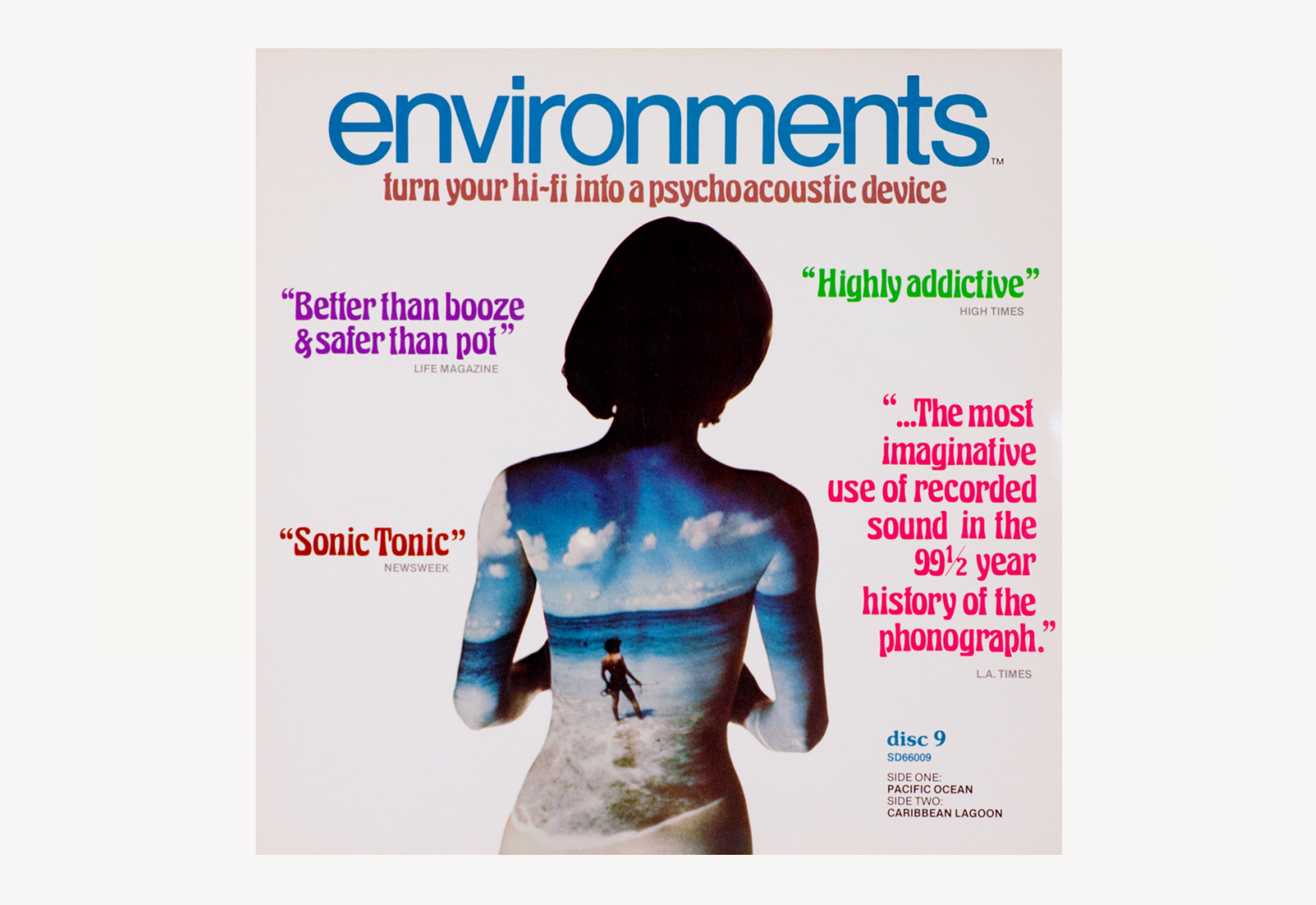

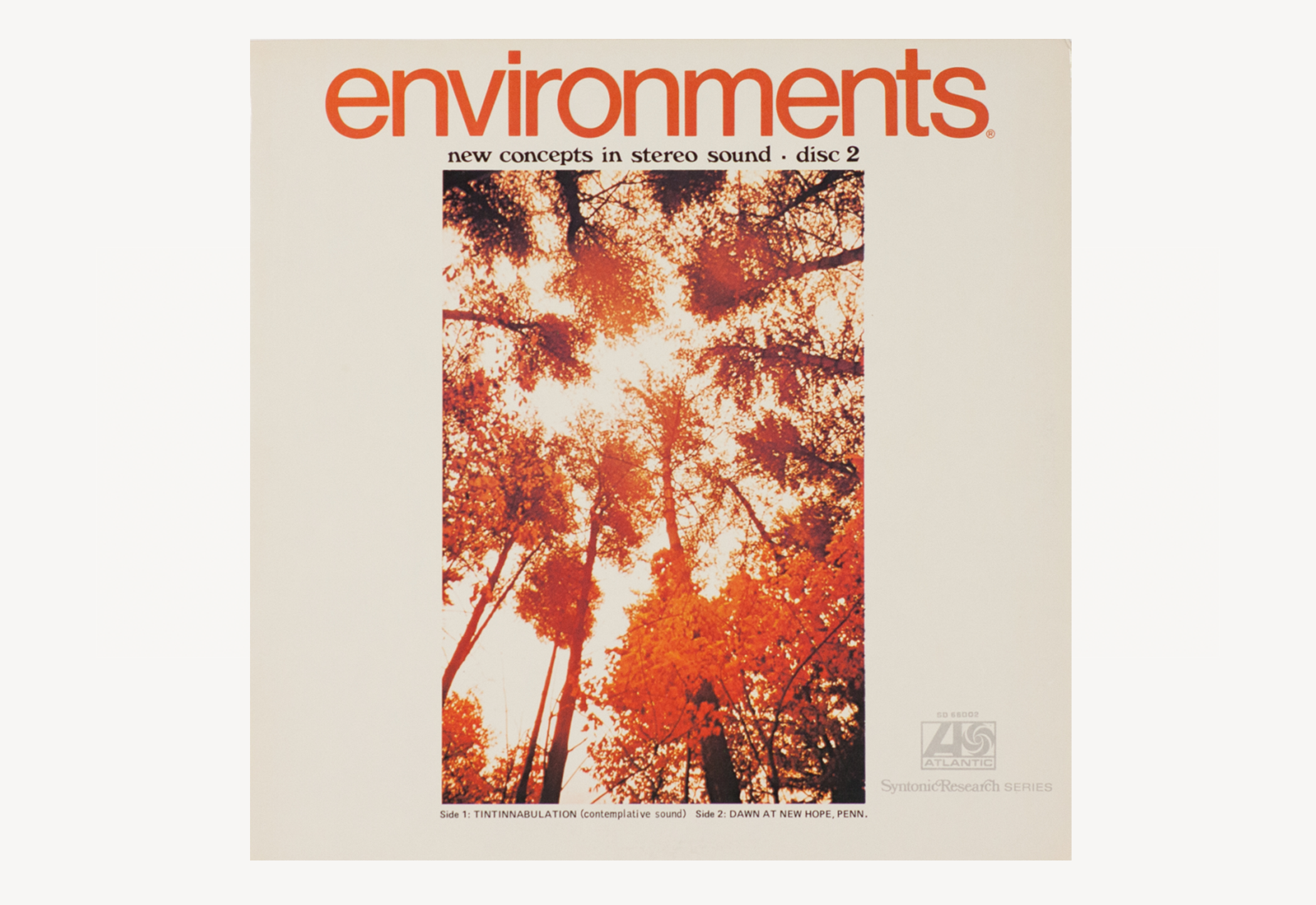

“The music of the future isn’t music”. Venture into just about any record store and there in a dollar bin you’ll likely encounter these words on the back of a vintage record sleeve. The front will be titled “Environments”, which was a groundbreaking – and contentious – record series of its time. Irv Teibel was the mind behind this 11-part LP series of “natural sound recordings” that helped usher in a new era of music. This new age movement in sound was marked by its consideration of a role and a certain set of benefits that music could offer its listeners; inspiring artistic creation, promoting relaxation and cultivating optimism. Teibel’s version of the genre also sought – and claimed – to offer a respite from the ever-increasing stresses of the modern world on the human psyche.

Each side of his LPs were dedicated to a certain setting: “Gentle Rain in a Pine Forest”, dusk in a Georgia swamp, the soft hum of insects on a cornfield, gentle waves rocking against a wood-masted sailboat. The concept proved quite successful in 1970s America, an ode to the spirit of the era. Students would use the recordings to study, others to sleep or relax. Some testimonials (never verified for their authenticity) claimed that listening to Environments enhanced sexual performance. But the hype couldn’t last forever. Decades later millions of copies now gather dust on record store shelves, a project largely overlooked until a group of music researchers from Chicago decided to pick up where Teibel left off.

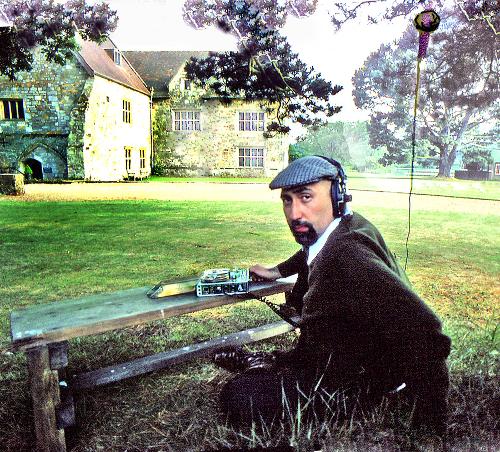

Teibel’s obsession with perfecting field recordings began when a friend commissioned him to capture the sounds of waves along the Coney Island shore for a film project in 1970. Back in his editing room, he became entranced by the loops of these recordings and later returned to Coney Island in an attempt to re-record the sound captured in his head. After several tries with disappointing results, he set out to instead “perfect” the sound of the ocean.

The irony of the association of Teibel’s infamy in championing these “natural sound” recordings is that the recordings were not really natural at all. “Teibel presented nature not as it is, but as we hope it’ll be, the lullaby of waves without the sand in our trunks,” music critic Mike Powell wrote in a 2016 piece on Teibel’s life in Pitchfork. The IBM 360 was the piece of technology Tiebel used to remix his field recordings, a clunky machine resembling that of a NASA shuttle compartment. The resulting product was an idealized memory of nature, one that he was passionate about championing as a wellness tool. In Teibel’s time (he died in 2010), little research had been conducted on the effects of sound on peoples’ moods. That’s changing. Numerous studies now suggest mental health and natural-world sound to be inextricably linked. The Biophilia Hypothesis offers an evolutionary explanation to this phenomenon, where certain environments equated survival to a dawning humanity: a running stream offering clean, bacteria-free drinking water, or chirping birds signalling the absence of predators, providing our ancestors an environment to rest. Sound is one of our most intimate senses; pre-birth we can hear before we can see, and certain sounds act the way scent does, with the ability to prompt involuntary memory teleportation back to a particular place or moment.